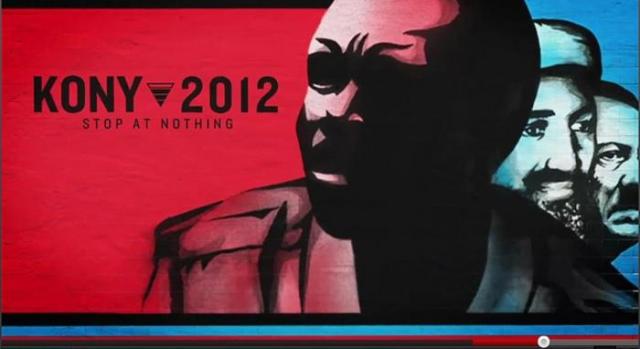

The social media IR story of the week was without doubt KONY2012, the 25 minute-long video produced by the NGO Invisible Children to draw attention to the use of child soldiers by the Lord’s Resistance Army in the conflict in northern Uganda. Love it or hate it, there’s no denying it has been a truly remarkable example of viral marketing. In the space of less than a week it was viewed by 112 million people. It prompted a KONY2012 drinking game and even Shane Warne tweeted about it!

What does any of this actually mean? How should we judge the work of Invisible Children? Have they succeeded in their mission simply by raising awareness of the war in Uganda? Or have they perpetuated a myth of a helpless child-like Africa, dependent on the assistance of the white, liberal, rich world to save itself? Do they send a message that the conflict can best be simply solved through military means, or that “saving Africa” can be done one wrist band at a time? Even if you think it’s well-intentioned, does Invisible Children actually make more difficult the work of people on the ground who have to deal with the LRA and the Ugandan government?

Did you get bombarded with KONY2012 stuff this week? What did YOU think? What does KONY2012 say (if anything) about the way the international agenda is shaped? How does it frame the conflict and the range of possible responses? I’ll keep my own views to myself for the time being, but must say I thought this particular Invisible Children Glee-inspired video was a crime against humanity all of its own.

I haven’t watched it, in part because i have been bombarded by it from flatmates to Facebook. I was told that i need to watch it and spread the word to other people because bringing awareness on the subject will (i don’t think the person telling me this knew how) fix the issue.

Who that person thought would fix the issue and by what means i don’t know. I should probably ask them.

The video itself is a social phenomena and can be contextualized as just that. Of those 112 million people who watched how many actually have the ability to affect change? I think it’s more of a Youtube sensation than a movement to improve the lives of child-soldiers. It’s more attractive to participate in the social experiment than the social reality.

And yes, it does perpetuate the myth that wealthy whites are the last best hope for saving Africa. If the video had been a sensation within Uganda and Africa first and that’s how the wider world discovered it then perhaps not (and i don’t know for certain that wasn’t the case – i’m just guessing it wasn’t), but since there are posters on our campus here at Vic about it and the video only came out two weeks ago i think my assumption is safe.

To be honest, i don’t think i will watch it. Does that make me irresponsible? Must i if i’m studying IR? I’ll probably try to finish this weeks readings first.

Strange side note:

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2012/mar/16/kony-2012-campaigner-detained

wow. they really are keen to keep it in the news.

But does it actually keep the real issue “in the news”? Presuming it wasn’t a stunt, perhaps this spazz out of britney spears’ proportions just takes it all to an easy, familiar and digestible level for most people, and in doing so, ultimately loses touch with the initial issue altogether. Said spazz out will be remembered and discussed longer than the video I reckon!

Unless you are a digital hermit it was rather difficult to avoid hearing and/or reading about it. There have been a number of posts and articles about the dodgyness of Invisible Children, the limited funds that they allocate to their charity and the high salaries that its directors enjoy. Beyond those issues I have to recognise that the campaign does raise awareness about an ongoing issue (and yes, in a rather the-West-will-save-Africa way). But so do a plethora of NGOs at local, regional and international levels, and they have a better understanding of the situation.

Invisible Children gives a simplistic, caricatural account of a 20-year-old conflict, with a touch of Hollywood drama – which probably explains the popularity of the campaign (the audience can put a face on the issue and relate to it) – but because they are in favour of a military intervention and financially support the Ugandan army (who in turn aren’t angels either), they aggravate the situation and undermine the efforts of NGOs on the ground.

I wonder what the humanitarian workers in Uganda and bordering countries thought of the campaign.

I am sure there are many different views on the video from humanitarian workers and other groups in Uganda, but this Al Jazeera report gives a bit of a sense of the response: http://www.aljazeera.com/news/africa/2012/03/201231432421227462.html

Being a faded luddite I also tried to ignore the sensation…

For me, the most interesting aspect of the KONY2012 phenomenon is not the huge budget, generalisations regarding the ongoing political and humanitarian situation in Uganda and the role of the LRA, nor the alarmingly slick production and even slicker Jason Russell, co-founder of Invisible Children (referred to recently in the media as a “clean cut, Abercrombie & Fitch version of Jesus Christ”).

What I believe is most pertinent about this latest global ‘viral’ information phenomenon to the realm of IR concerns the ease with which information can now be spread across the globe – unhindered by state borders, governments (for the most part), or differences in demographics, language, cultures and peoples. Information can spread with the speed of a click of a button across entire continents and, as was the case with the KONY2102 ‘virus’, was seen and absorbed by what must be approaching 120,000,000 people. Information, in its multifarious forms (whether formalised in officially sanctioned reports, popularised in films or even the spoken word), is a significant source of power. The hegemony of knowledge is nothing new (see Gramsci and neo-Marxists) – but what I argue here is that anyone now has this power, and it isn’t knowledge but rather sensation driven.

Critics of Invisible Children argue that the organisation, far from a liberal, humanitarian not-for-profit, non-partisan seeker of truth, is a covert semi-fundamentalist Christian organisation (!) What is postulated globally as a purely liberal/ Kantian altruistic desire for the world to rise up and free the children of Uganda from the oppressive Joseph Kony, is a thinly veiled publicity and revenue raising stunt. It is argued for example that only a third of funds donated to Invisible Children actually reaches Uganda – the rest appears to be funnelled into the organisation’s corporate and Christian campaigning. As such, what appears at first to be a (liberal-motivated) attempt to raise global awareness, and gain justice for the Ugandan people, is in fact a materialistic, institutional power play underpinned by realist intentions. Oh dear.

What I emphasise here is that the idea of the global NGO’s operating outside and above the anarchic hobbesian state system as impartial, ‘selfless’ driving forces for transparency, cooperation, liberalism and the ‘utopian ideal’ is flawed. They, as any institution, appear to be driven by very realist intentions of self-preservation, power and material gain.

My second criticism of the KONY2012 campaign is the inaccuracy of the information provided. Critics argue that neither Kony nor the LRA has been active in Uganda for over five years. He is believed to have fled to the Central African Republic, where he is said to still operate, as well as within South Sudan and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. What I believe is of relevance here is that as we (the public, scholars, governments and increasingly trans-national organisations and global institutions) become increasingly interconnected and involved in the structures and mechanisms of international dialogue and governance, we come to rely ever more heavily on a diverse array of information sources. Organisations like Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, or Minorities at Risk provide us with what we hope is credible information upon which to base the conceptualisation and implementation of global structures and norms. If the information we are privy to is inaccurate or biased, so will be the decisions we make.

Interestingly, on Wednesday we saw the momentuous occasion of the first verdict made since the International Criminal Court was created a little under 10 years ago, with Congolese warlord Thomas Lubanga found guilty of recruiting and using child soldiers between 2002 and 2003.

The role, responsibility and ability of an international (western) court to preside over the ‘dark continent’ and the wider global realm has (finally) been formally validated, but whether the easily swayed rhetoric of the global community can manifest in serious, positive steps forward in transparent and effective global governance structures and institutions remains to be seen.

Andrew, thanks for the post. We’ll be examining how and why some issues get taken up by NGOs (and some issues don’t) when we come to our week on transnational activism, but Charli Carpenter has an article in International Organization in 2007, looking at issues like children born of wartime rape (and why this hasn’t been picked up by NGOs) that comes to some conclusions not far from your own, i.e. stressing institutional self-interest. I guess the one line I take issue with in your post is the claim that with the spread of social media “anyone has the power” to mobilise action. Does “anyone” have access to these technologies and to these particular strategies of persuasion? And thinking in terms of “sensation” as a particular (Western) cultural construct, who gets to produce these sorts of claims?

There’s no denying the polarising impact of KONY 2012 and all the attendant complexities of the issues it raises. Like many people, I was oblivious to the existence of Joseph Kony and the LRA until the video went viral on Facebook and set off a chain reaction of comment in the blogosphere.

Jason Russell frames his film as a social media “experiment” which is designed to “change the conversation” and given the furore it has provoked and the fact that he has brought Kony to the mainstream attention of the West, I think the video/movement is a qualified success on those terms. He has elevated the tragedy of child soldiers to a level of debate that may bring about some real change if there is a responsible reaction from world governments/institutions to the issue – and Thomas Lubanga’s conviction by the ICC last week for war crimes suggests that justice may be possible in Kony’s case too.

In terms of raising consciousness about Kony and the LRA, I saw merit in both Michael Moran’s take:

But the sanctimony of modern, main-stream journalism—particularly American journalism—is unbearable on this issue. Given the paucity of serious foreign coverage in the U.S. media, can we blame anyone for using the tools of modern media to get around the commercial filters that masquerade as “editorial judgment” these days? How many U.S. news organizations can claim to have had any impact with their coverage of the LRA or even Uganda in general in the past decade? The list of those that even bothered trying is less than a dozen.

The critics so quick to tear down Invisible Children should, in fact, be studying how they managed to reach such a wide audience with this story rather than complaining that the video didn’t meet their standards. Whatever the simplifications, the LRA kidnaps children for use as sex slaves and child soldiers and has raped and murdered its way through a three-country swath of central Africa for a generation.

And MacDonald asking : Will simplistic explanations of long-running wars, delivered in a Facebook-friendly manner become the future of foreign policy?

Is it enough for Russell to have started the conversation around Kony even though his narrative is problematic for a number of reasons: the crowdsourcing of military intervention (not to mention the factual discrepancies eg. Kony not actually being in Uganda), emotionally-manipulative oversimplifications, ethnocentrism (eg. perpetuating the White Saviour Industrial Complex) and the well-documented concerns around the financing of IC? Or is the issue so nuanced that only the ‘experts’ (rather than social activists) should be qualified to effect change? It’ll be really interesting to watch this play out.

Rob, a really thoughtful post and many very good points, particularly about the pious nature of some parts of the media who it might be argued engage in precisely the same “White Saviour” media tactics when they try and “sell” the latest war, famine or crisis in other parts of the world. I agree with much of what you’ve written, but for me, the most damning criticism of IC has come not from the Western academics and media, but from the NGOs and local groups working in northern Uganda and the DRF to free people from the LRA, who argue that the KONY2012 campaign and calls for military action actually make what they are doing much, much harder. My friend Erin Baines has spent years working in Gulu, has met Kony, and here’s what she had to say about this issue: http://justiceandreconciliation.com/2012/03/ugandans-2012-canadian-international-council-12-march-2012/

Whilst I was initially disgusted by this meme (and in the long run I suspect that is all it will be), I have to admit that I am also very fascinated by it. I also have to say that while I also found it arrogant, patronizing and naive it didn’t surprise me in the least: It is a typical example of the (postmodern?) age we live in, and just another example of consumer activism. It is activism from a distance that has resulted from the collapsing of space due to technology, and that had it’s inception (I think) in campaigns like Live Aid in 1985: Social consciousness managed as a media event where we return to the outrage at hand “right after these messages…”. It is outrage without commitment. From a global governance perspective I sometimes wonder (and worry) about the consensus of global civil society, where there appears to be a digital divide prevailing. Foreign intervention for/by the Facebook generation, anyone?

I have heard a lot of arguments defending the Kony2012 campaign saying that it is at least raising awareness of what is going on. As a ‘conversation starter’ it has certainly been an unqualified success. But in this age of multi-channelled infotainment I suspect that it is a conversation that will cease as soon as the next outrage mediated by Facebook, and ‘liked’ by the masses, comes along.

A half hour clip ‘detailing’ the atrocities of Kony in Uganda? I have seen it and, admitting I didn’t know much about it before hand, I suspect that not only is it oversimplified it has set up false expectations of solutions. This situation requires a nuanced solution encompassing diplomatic, humanitarian and military approaches. This is a campaign focussed on child soldiers that is unfocussed on the entrenched poverty and historical machinations that helped create Kony.

Now where can I get a wristband?…

Interesting post by a humanitarian worker I used to work with: http://philvernon.net/2012/03/14/kony-2012-is-slacktivism-enough/

Thanks Sengad, I’m clearly a digital hermit as I hadn’t heard about this latest viral stunt;) Firstly, I have to say that the NGO is smart in creating a video and putting it on Facebook and other social media – I presume the filmmakers volunteered their time for free. International organisations and NGOs waste millions on awareness-raising brochures and glossy fliers that only end up in recycling bins. At least, as Rob says, this has raised awareness about a particular abhorrent issue, most prevalent in Central Africa. True, this is hardly going to change foreign politics and hopefully won’t reduce foreign policy-making to one-issue campaigns led by evangelicals, but bringing warlords before the International Criminal Court is something to be encouraged, right?

However, raising the status of international criminals to famous celebrities is a senseless strategy, not to mention the mindlessness of not involving those who suffered at the hands of Kony. If this NGO were really serious, it would know the importance of working with its stakeholders (cliche I know, but true), in this case the key group being those Ugandans still living with the scars. The Al Jazerra report showed just how incensed they were with the film.

It is rather ironic that the film was made in the US, which is not a State Party to the ICC. Wouldn’t the NGO had been better to round up its ‘army for peace’ to pressure the US into ratifying the Rome Statute? Or they could have spent their energy in pressuring US policymakers on major issues of the ICC such as territorial/universal sovereignty. That could have far more impact on war crimes, genocide and other crimes against humanity than turning a warlord into a star. Surely, as stars of the film themselves, they understand the appeal of being a star…

SPK915 – Live Seminar 44: Social Media as a Tool for Humanitarian Protection, Friday 11 May

Content

11 May, 1:30am, online

The next in the Program on Humanitarian Policy and Conflict Research’s series of web seminars will see expert panelists and participants examine the key developments, challenges, and critiques surrounding social media’s impact on humanitarian protection. Register here: http://www.hpcrresearch.org/events/live-seminar-44-social-media-tool-humanitarian-protection